What could go wrong? If Lowe’s will sell me a Dow “Froth-Pak” for $747, it must be easy enough to do. And I am not completely without experience. Over the years I have emptied many a can of “Great Stuff” expanding foam into my rafters, my window casings, my hair.

What could go wrong? If Lowe’s will sell me a Dow “Froth-Pak” for $747, it must be easy enough to do. And I am not completely without experience. Over the years I have emptied many a can of “Great Stuff” expanding foam into my rafters, my window casings, my hair.

Basement insulation may seem like a digression from the subject of the Great Heat Pump Update, which went well. It took about three long man-days to install five heads and an outdoor unit, which gave me pause: I had considered installing those myself, as is my habit, after seeing that you can buy a unit for $700.

No. Freaking. Way. There are faaaaar more parts than they show you in the Lowe’s advertisement. And the installation involves a huuuuuge amount of wall-boring, and electricity, and yarding seven tubes through a hole that’s only big enough for four tubes. That assumes you sized the whole system correctly in the first place. If you don’t size your system correctly, forget about the amazing efficiency you hoped to gain. You might as well give Lowe’s your $747, jump into a thorn bush, smash some spiders into your hair, then throw the heat pump in the trash: You’ll achieve the same effect, but save a lot of time.

But that went fine. The system is silent, steady, and unobtrusive. Don’t talk to me about “ugly things hanging on the wall.” If humankind can get used to colossal steam radiators that frustrate any furniture plan, and rusty baseboard radiators snaking around a room, and air ducts in the floor where you can look down and see 20 years’ worth of dog hair and Cheerios, I’m confident that we can think of something uglier than heat pumps to complain about.

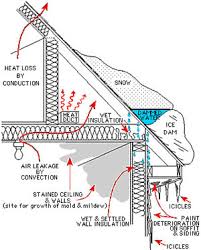

And basement insulation is actually not a digression from the subject of heat pumps. Where once a few tons of iron furnace and piping shed heat into the basement, there now is no heat at all. But the household plumbing is still down there, at the mercy of the approaching winter. The field-stone foundation, its mortar gone dusty with time, doesn’t mount much of a defense.

Hence the need for foaming. There is now a heat pump head down in the basement, to protect the pipes. But I’ll be damned if I’ll ask that thing to heat a field-stone foundation, and the frozen earth beyond. There must be insulation. What kind, and installed by whom, to be determined. There are two haz-mat suits in the kit. Just putting that out there.

The massive pipe wrench showed promise at first but most of the giant nuts were stuck tight, and would not budge. One did. It was satisfying.

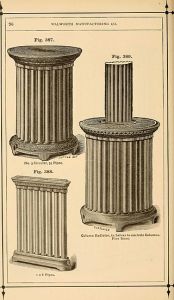

The massive pipe wrench showed promise at first but most of the giant nuts were stuck tight, and would not budge. One did. It was satisfying. We descend below-decks, and attack the steam pipes. They criss-cross the basement ceiling, and meet in a massive octopus tangle at the (dead) boiler. One blade, in our amateur and shaking hands, can gnash about 500 pounds of Fe into sections that we can haul out of the basement. Performed correctly, your work should look like this. Note that three of the five blades snapped at the base; one is MIA completely. In hindsight, it’s remarkable that we did not accidentally Sawzall the following: a gas line; a water line; an electric wire; each other.

We descend below-decks, and attack the steam pipes. They criss-cross the basement ceiling, and meet in a massive octopus tangle at the (dead) boiler. One blade, in our amateur and shaking hands, can gnash about 500 pounds of Fe into sections that we can haul out of the basement. Performed correctly, your work should look like this. Note that three of the five blades snapped at the base; one is MIA completely. In hindsight, it’s remarkable that we did not accidentally Sawzall the following: a gas line; a water line; an electric wire; each other.

And for OPERATION HOLE PLUG. You’ll often see these steam scars in old houses, plugged in various ways, with varying aesthetic results. The floor has been refinished around the radiator feet, which will add to the challenge.

And for OPERATION HOLE PLUG. You’ll often see these steam scars in old houses, plugged in various ways, with varying aesthetic results. The floor has been refinished around the radiator feet, which will add to the challenge.

My husband didn’t hear me the first 200 times I said, “Add water to the steam boiler reallllly slowly.” He’s from a part of the country where the populace prefers less catastrophic methods of home heating. So when the boiler quit due to low water, he descended to the basement, located the cold water valve, and let ‘er rip.

My husband didn’t hear me the first 200 times I said, “Add water to the steam boiler reallllly slowly.” He’s from a part of the country where the populace prefers less catastrophic methods of home heating. So when the boiler quit due to low water, he descended to the basement, located the cold water valve, and let ‘er rip.

This picture is worth a thousand words. Just do this, and you won’t have to read the rest of the post. But by all means if you prefer reading about stuff you should do, rather than actually doing it, read on. We’ve all been there.

This picture is worth a thousand words. Just do this, and you won’t have to read the rest of the post. But by all means if you prefer reading about stuff you should do, rather than actually doing it, read on. We’ve all been there.